Given some runway, students take flight

February 12, 2024

“Aerospace research,” the UVic Co-op posting said.

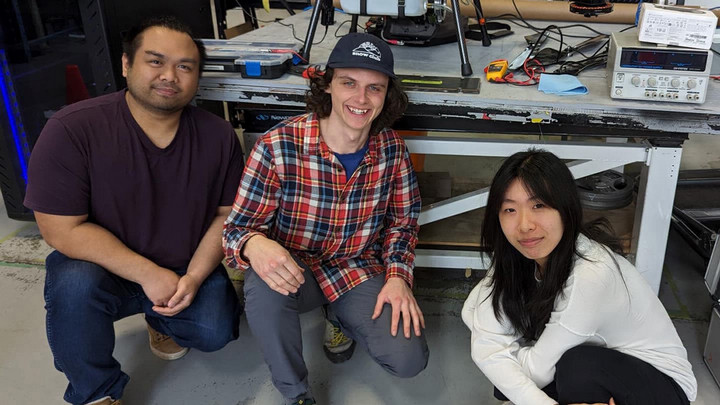

Who wouldn’t be intrigued? Third-year UVic electrical engineering student Mclaine de Jesus certainly was.

And once he got the job, it just got better: He discovered an unexpected culture in the hangar at Victoria International Airport.

“We are given the ability to undertake a whole project on our own,” says de Jesus, who is now in the midst of his second co-op work term at UVic’s Centre for Aerospace Research, CfAR.

Chantel Guo, a fellow co-op student at CfAR, adds that is a major part of what she loves about her first co-op work term. When she finished her second year of electrical engineering at UBC, she wanted practical experience.

“CfAR is very much an R&D organization,” she says. “I have the freedom to do design work and experiment with my own ideas.”

CfAR was founded in 2012 by mechanical engineering professor Afzal Suleman “to spur innovation and attention to the positive role Unmanned Aerial Vehicles [also known as drones] can play in betterment of society.”

A Canada Research Chair in Computational and Experimental Mechanics, Suleman is globally renowned for his leadership in next-generation aerospace transportation systems and aeronautical design. For many hundreds of students, though, he is a global leader in teaching and mentorship.

“Students have always been the driving force,” he says. “They are the legacy.”

Forty PhD students, 150 Master’s students, 20 post-doctoral fellows and possibly over 200 co-op students have used the research and education opportunities he has provided to design and build their own wings — or store them.

Fourth-year mechanical engineering student Brian Mueller has been building drones since he was 13; he’s even taught kids at drone camp. After a friend recommended it, he applied to work at CfAR and when he set foot in the facility, housed at Victoria International Airport, he was hooked.

“There are so many tools in the shop and there’s time to learn how to use them,” he says. “I wanted to get the hands-on experience from design to manufacturing. You get to do it all and contribute to the team’s larger projects.”

Instead of focusing on designing and building drones, these days he’s tackling something different. During this, his second term in a row at CfAR, he’s designed and is building a storage and transportation system for the prototype Bombardier EcoJet. The steel structure will hold the components of the blended wing body aircraft inside a shipping container.

Although the undergraduate students are given a lot of runway, there are more experienced students and professional engineers around to help.

“We design the project and present our ideas to the team, there are design reviews with the more senior students and supervisors,” says de Jesus.

Guo is designing and testing a communications system that reads data from the wings and sends it through a micro-controller to other aircraft systems such as the autopilot. De Jesus is completing a backup power system that monitors the main battery pack and switches over when needed. Next, he’s looking forward to upgrading the avionics inside the plane.

If that sounds like a lot of responsibility for students still in their early 20s, it is. And the students are carrying it.

Jay Matlock, the manager of CfAR, says, “We provide the team members with the tools and resources they need to be innovative. We give them a healthy amount of responsibility and challenges right away. Dr. Suleman started that culture.”

Matlock’s philosophy has two wings. First, at CfAR they’re empowering problem solvers. “We do as much hands-on learning as possible, to bring to life everything you’ve learned in theory. If you have an idea on Monday, we try to implement it by Friday.”

And second, “Everyone teaches each other as we try to solve complex problems together as a team.”

Matlock started at CfAR as an undergraduate himself nine years ago, then was hired as a full-time engineer and completed his Master’s program at the same time. As one comes to expect at the hangar, he took on more responsibilities and expanded his skill set until now, “I think I might have the best job in the world,” he says of working with a diverse team ranging from research engineers, Transport Canada-certified Remotely Piloted Aircraft System Operators and PhD and Masters students from around the world, to young researchers getting their first taste of what’s possible.

“CfAR’s whole environment lets us experiment with our own creations,” Guo says.

De Jesus agrees. “They tell us ‘the world is your oyster—go for it.’”

“When it comes to innovative students and ideas to help shape the future of aviation,” Jay Matlock says, “CFAR’s hangar doors are always open.”

-30-

Rachel Goldsworthy