Expert Q&A on Shakespeare and 400th anniversary

- Tara Sharpe

April 23, 2016 is the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare's death.

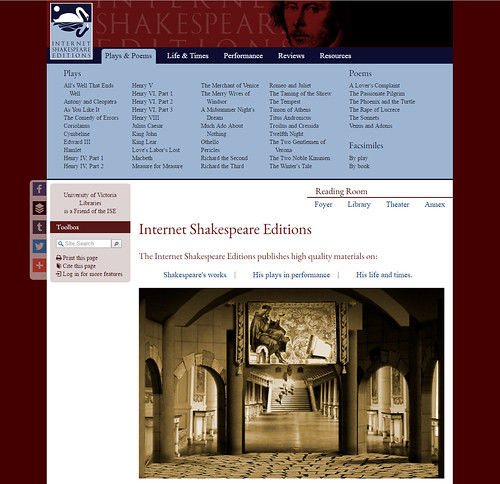

Professor Emeritus Michael Best - an early trailblazer who launched Internet Shakespeare Editions (ISE) in 1996 even before the world-wide web totally swept the globe - explains the lasting impact of Shakespeare's oeuvre and why people remain enamoured with the Bard of Avon.

UVic is a leader in the fields of Shakespearean study, Renaissance literature and digital humanities, and its English language and literatures programs are ranked in the top 200 in the world by the QS Subject Rankings.

Click here for a sample list this month of additional UVic expertise on Shakespeare and digital humanities.

Why is Shakespeare still so important four centuries after his death? Why him, and not Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson or any other well-known English playwright?

Simple answer: Shakespeare was the greatest - the best.

Also, he produced the largest corpus; therefore, through his work, we get to know him: we see him in all manner of moods - from playful to nihilistic. His is a kaleidoscopic, fascinating variety.

It's true it wasn't only Shakespeare in Elizabethan London. The writers and playwrights of the time developed a culture in which rich thinking was part of the entertainment. And Elizabethan audiences loved language, the rich sounds.

Shakespeare does great entrance and exit lines. Actors love the plays and Shakespeare was an actor. He knew what actors wanted.

What would you ask Shakespeare, if you could travel back in time?

I would ask, how did the plays evolve? How much of each play was edited while being staged?

There are multiple existing versions of some of the plays. In King Lear, the play I'm editing, two versions differ sometimes by about 400 lines and some speeches are assigned to entirely different characters.

In Shakespeare's day, plays weren't treated as serious literature. Later that changed. But the quarto version of King Lear, printed before the First Folio of 1623, was clearly produced from a messy manuscript and by inexperienced compositors (typesetters) who had never printed plays before.

It's quite a challenge to tidy up. On paper, reading two different versions of one of Shakespeare's plays is like watching a tennis game.

Digitally, we can present one version and then flip easily to the next. And unlike standard editions, the ISE can provide in-depth exploration through links, video, music, graphics and background materials relevant to the interpretation of individual scenes.

Where do you think Shakespeare would fit in today, in 21st century London?

Many of Shakespeare's plays were collaborative, much like the TV script writing of today. And he was somebody working actively in what was then the only popular entertainment in London. So maybe today he would be a brilliant script writer. The parallel with TV scripts is not a distant one.

Ours is a very visual culture. Shakespeare and his contemporaries were very verbal. For instance, there are lines in popular plays of the period that are simply lists of names of exotic places. But if his audiences loved the sounds of Early Modern English, how would that method translate today?

It's not easy to combine popularity with intellect and quality as he did, with good writing and acting.

Why did you start the ISE?

I was working in the digital world back in the '80s. When Apple brought out a program called HyperCard, for the first time you could click on a word and there would be an action or association. And that's how I think. When I see something, I want to go there.

Exploration is what this medium supplies - that's what this business of 'clicking' allows. As a teacher, I wanted my students to cultivate further exploration of the material. The web has made all this easy now, but it was very new then.

What did the technology look like then?

The ISE started as a series of Macintosh floppy disks [containing a computer program called Shakespeare's Life and Times] allowing students to jump with a 'click,' for instance, from a page to a bibliography. Once I'd done that, I wanted to develop it further - as a CD-ROM with graphics and videos. And then, in 1995, for the first time, a webpage could support the display of an image. I thought, "OK, the CD-ROM is dead. This is what I want to do now."

What do you see as the future of the ISE?

The digital world is changing fast. We ensure continuity and stability by using open source software, and by encoding our work in standards-compliant ways that ensure that whatever we create now can be understood by machines far into the future.

The future is in digital publications open to all. But it takes energy and commitment.

I see the ISE's future as secure in a number of ways. Young and digitally-savvy scholars are engaging in the project, notably my colleague Dr. Janelle Jenstad, associate professor in UVic's Department of English, project director for the Map of Early Modern London and associate coordinating editor of the ISE (currently on leave). The university is committed to continuing and growing the project. The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada has provided three major grants for the ISE.

There is one continuing challenge: we need constantly to be updating and improving our site - and this takes money. So we have launched a fundraising campaign, "Making Waves," to encourage visitors to the site to become "Friends of the ISE" and we hope in time we will be able to establish an endowment to ensure there is continuing funding for student programmers and research assistants to continue the process of updating and enriching the ISE.

The ISE is an open-access, peer-reviewed scholarly website with leading experts on its editorial board. The site has been visited by millions of people in the past 20 years and each month it registers over 2 1/2 million downloaded pages - giving fans, scholars and actors around the world unprecedented access to the works and words of the Bard.

Best is a former chair of the UVic English department and founder of the ISE. Although officially retired for more than a decade, he is still active with the ISE and is currently editing a digital version of King Lear.

- Read more about Best and the department: 2012 profile 2009 award in digital humanities

- Visit the ISE site (http://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca)