New civil engineering department poised to lead a green industrial revolution

- Suzanne Ahearne

When UVic’s civil engineering program first launched in 2013, nested in mechanical engineering, its intent was to grow into the go-to program in Canada for green civil engineering. Under the direction of new chair, industrial ecologist Chris Kennedy, the fledgling department is taking a big step forward.

“Climate change is a shared societal challenge and everyone has to contribute to finding solutions,” says Kennedy, formerly of the University of Toronto. Some of the main causes of emissions—transportation systems, buildings and waste facilities—are the core things that civil engineers design. And because of heavy reliance on steel and concrete—cement being a major cause of greenhouse gas emissions—civil engineers need to take a bigger leadership role in the climate change challenge, he says. “There has to be a green industrial revolution.”

UVic’s civil program—its first class of 41 students will graduate in 2017—is focused around four strategic areas, all centred on making the best use of natural resources and lessening environmental burdens: green buildings, sustainable cities, industrial ecology and water resources.

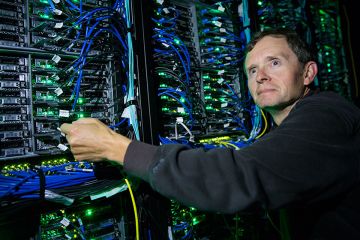

Recruitment of world-leading researchers in the forefront of these fields has already begun. Currently, the department has expertise that includes groundwater systems, innovative construction materials, energy-efficient buildings, steel structures, transportation system modeling and urban stormwater. The goal is to have a faculty of 15 within three years.

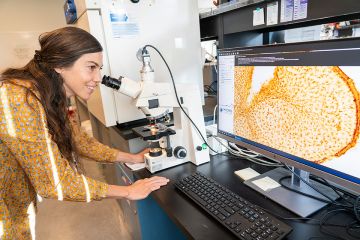

“We would like to achieve a 50/50 gender split in both faculty and students,” Kennedy says. UVic now follows close to the national trend, where 22 per cent of civil engineering undergrads are female. National female enrolment numbers are higher for biomedical engineering and lower for electrical, mechanical, software and computer engineering, UVic’s other engineering disciplines.

Dean Tom Tiedje sees the department as a great fit with UVic’s environmental ethos and he envisions collaborations with other engineering departments, and units such as Environmental Studies, Earth and Ocean Sciences, IESVic and PICS.

“We hope for impacts in many ways,” says Kennedy. “Our expertise will have impact on cities and communities in BC. One way is to help develop strategies and inform building codes to decrease energy consumption of buildings.”

Before the program launched, the school received 40 letters of support from employers on Vancouver Island and elsewhere in BC who told the school that they have trouble finding civil engineers.

“By establishing a new engineering program, we are creating opportunities for BC young people to have rewarding careers in good paying jobs while enabling growth in the province’s technology-related industries,” says Tiedje.

In BC, the average age of civil engineers is 50—the highest in the country—and

labour market projections show that in BC and Alberta, the numbers of civil engineering graduates falls short of expected job openings. Of the four civil programs in the province, UVic is the only one that’s 100 percent co-op.

Student demand for the new program is already strong: after the civil program was established in 2013 (alongside biomedical engineering), domestic student applications doubled. At the same time, the percentage of female students entering UVic’s Faculty of Engineering also doubled. The department expects to begin accepting graduate students this year.

By 2050, the world’s population will be close to nine billion and the economy is expected to quadruple, with much of that growth in cities in India, China and Africa. “As grad students come here to study with our internationally recognized researchers in sustainable cities and building design,” says Kennedy, “we can make a big difference in how these booming cities are being planned and built.”

Photos

In this story

Keywords: civil engineering, administrative