Makerspaces matter

Update (Oct. 28, 2015): The first Kit for Cultural History was unveiled this month at Rutgers University in New Jersey. The kits will also be presented Nov. 20 at 12:30 p.m. in UVic's David Strong Building (room C116), with physical copies being sent to universities across North America.

Maker culture at UVic

The Maker Lab at UVic, housed in the Technology Enterprise Facility, is a collaborative space of new techniques and old technologies involving the invention of imaginative and often outsized revisions of objects that don't always exist in the world. Because its research is innovative, multi-faceted and occasionally intangible, it does not easily fit a simple definition.

The lab is inspired by experimental art, design and D.I.Y. cultures. The inter-disciplinary research team from UVic English, CSPT and Visual Arts includes faculty as well as undergraduate and graduate students who use physical computing and digital fabrication for cultural research.

The lab was launched in September 2012, under the leadership of director Dr. Jentery Sayers, an assistant professor, English and CSPT, with funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, Canada Foundation for Innovation and the British Columbia Knowledge Development Fund.

The Kits for Cultural History project (spanning four years, from 2013 to 2017) is a tangible example of what is being created in the Maker Lab. Supported by a SSHRC Insight Grant, the project is led by Sayers, with support from Dr. William J. Turkel of Western University.

Its core content is obsolete technologies and media. For instance, one kit includes a Victorian innovation-a late 19th-century decorative stickpin, by fringe engineer and designer Gustave Trouv&e#180;, that may never have functioned properly-recreated 100 years later by the UVic team.

Technologists as magicians

Trouv&e#180; was as prolific as Edison, but did not have the same 'business' agenda. Most of Trouv&e#180;'s fashion(ed) pieces of the mid to late 1800s were meant to be movable or animated, but only one working artifact exists now, prompting the UVic team to wonder what actually worked then.

Trouv&e#180;'s pin is now glassed off in a display case at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London; few people can touch it.

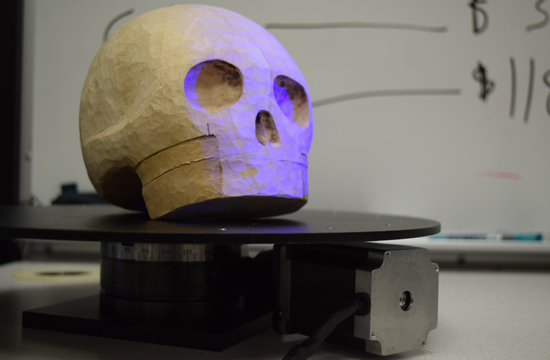

The hands-on learning for the UVic team involves one of the main methodologies in the lab: to transform analog artifacts into digital content and then back into tactile form, such as the large-scale skull replica from the Trouv&e#180; stickpin (the replica was carved in wood at roughly ten times its original size-see above image).

The lab is remaking and reinvigorating antiquated technologies-which are no longer accessible and perhaps never functioned properly in the first place-by creating high resolution 3D models and manufacturing them with computer-controlled machines. "Put this way, the Maker Lab actively intervenes in the stuff of material history, determining what is missing and then circulating physical prototypes of the absences for interpretation," says Sayers.

It continues to borrow from traditions in cultural criticism, including studies of how technologies are intertwined with labour and power. But it also embraces experimentation and consequently reminds us that many technologists of the Victorian period were also, to quote Sayers, "brilliant magicians."

This year, the Maker Lab plans to send 15 to 20 kits via Canada Post to colleagues at universities across North America. The stickpin will be included.

Intersecting cultural criticism and computation

Sayers describes the Maker Lab as an "intersection of cultural criticism and comparative media studies with computation, prototyping, electronics and experimental methods. Its design is anchored in blending a humanities research lab with a makerspace-a design that affords its team of students and faculty opportunities to build projects through various modes of 'knowing by doing,' such as programming, markup, new media production, data modeling, 3D printing and circuit design."

The lab's research will ultimately "inform policies on the ethics, distribution, licensing and derivation of 3D objects," says Sayers, policies which currently do not exist in Canada. The lab also trains students in physical computing and desktop fabrication in non-STEM fields. Sayers points out that fabrication and physical computing are popular in STEM fields, but are virtually unknown in the humanities.

Digital Fabrication Lab in Visual Arts

The Digital Fabrication Lab (DFL), an extension of the Maker Lab, is now open in the Visual Arts Building. While the TEF space works well for the prototyping side of Sayers' research, it is not sufficient for digital fabrication and machining. The DFL is the first lab of its kind to encompass the arts and humanities in North America.

Additionally, no university or college in North America yet has a computer numerical control (CNC) lab in the humanities, meaning the DFL is the first humanities facility of its kind on the continent.

"There are far-reaching effects for this type of technology in just about everything we do," says Department of Visual Arts chair Paul Walde. "Photography was the first area where there was almost a complete paradigm shift towards digital, and we're now seeing digital technology move into every aspect of visual arts production. This represents a way for us to move forward not only with new sculptural techniques and projects but also printmaking and even certain kinds of painting."

The DFL will include CNC routers, an industrial grade 3D scanner, a laser cutter, a milling machine, and 3D printers, together with various machining tools. "Visual Arts is a leader in material practices and material culture," says Walde, who notes they already have extensive workshops and the necessary support staff to expand into this area. "We have purpose-built facilities for the safe handling and research of these applications. It's a perfect fit for us…it's an investment in the future.

"I'm very excited about it. I can't wait to see what the possibilities are with this equipment. That's usually what gets the imagination stirring."

At the forefront of digital humanities

The Maker Lab and DFL are two of several initiatives at UVic-including the Humanities Computing and Media Centre (HCMC); Electronic Textual Cultures Lab (ETCL);Implementing New Knowledge Environments (INKE); Modernist Versions Project (MVP); Internet Shakespeare Editions; Map of Early Modern London; and the annual Digital Humanities Summer Institute-which continue to position the university at the forefront of digital humanities.

In a November 2014 talk at the University of Virginia on the topic of remaking Victorian miniatures, Sayers explained further what matters as scholarship in the context of makerspaces and the humanities: "Contrary to popular perception, remaking historical objects need not assume the exact replication of artifacts, an investment in high fidelity reproduction, appeals to authenticity, nostalgic fantasies of 'being there,' uncritical hobbyism, escapist immersion, an obsession with control, or a fetish for the analog.

"But I do think remaking is prompting many scholars to not only reconsider immersion (in combination with 'critical distance') but also rethink claims that the practice of history is (or should be) all exteriorities. In fact, for those of us in the Maker Lab, remaking is most often about what isn't at hand, or what we don't know, or what we're willing to conjecture."

The Maker Lab team also presents talks, publishes its findings and facilitates workshops.

Visit maker.uvic.ca to find out more.

For more on the DFL: http://finearts.uvic.ca/blog/?p=5062

KnowlEDGE column (October 2013)