Digitized early map of London continues to bridge time

- Tara Sharpe

You could walk across London of the 1500s in about 20 minutes. And now, thanks to the survival of a 450-year-old woodcut map, Shakespeare’s world can also "open up to us like a Google map,” says Dr. Janelle Jenstad (English), project director of UVic’s constantly evolving Map of Early Modern London (MoEML).

UVic Announcement: http://bit.ly/1bvT5ca

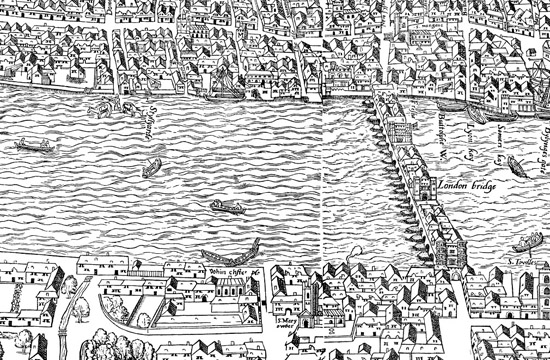

The Civitas Londinum, more widely known as the “Agas” map, was first carved into woodblocks in approximately 1561 and then printed on eight separate sheets of paper or “broadsides.”

MoEML’s history began at UVic in 2005 with an online grid map, after Jenstad brought the project from the University of Windsor to UVic's Humanities Computing and Media Centre (HCMC). The original map woodblocks and 1561 prints are long lost, but three 1633 copies of the Agas map survived into this century. One is in fragments at the UK National Archives in Kew. Another is framed and under glass in the Pepys Library at Magdalene College, Cambridge. The UVic team worked with a digital version of the third copy from the London Metropolitan Archives.

In January 2008, The Ring published an early update on the UVic project. Now freshly launched, Version 5.1 offers a high-resolution, experimental, Google-style, multi-layered iteration of the original MoEML map.

The UVic research team—including MoEML associate director and post-doctoral fellow Dr. Kim McLean-Fiander; MoEML lead programmer Martin Holmes of the HCMC – see Ring story on digital humanities at UVic; UVic alumna and research affiliate Sarah Milligan, now the publishing manager at British History Online; and numerous UVic graduate and undergraduate students—took a version of the old relief map and transformed it into an online equivalent that is highly interactive and saturated with layers of textual analysis and pictorial information.

Stitching it all together

After negotiating with the London Metropolitan Archives to obtain the high-resolution map images in late 2013, McLean-Fiander spent the next year with the rest of the team researching the “seams” or gaps between the eight pages (from the original eight woodblocks) and determining how best to stitch them together digitally.

Much like worn wooden blocks, the 17th-century paper had been worn down too. The MoEML team worked to fill the gaps by lining up the page images and gathering evidence from other maps and documents from the period.

McLean-Fiander and Jenstad collaborated with local artist Jillian Player to reconstruct on long strips of paper the missing map pieces. Then, the strips and images were digitally stitched together and thousands of tiny digital adjustments were made by Greg Newton of the HCMC.

Finally, Holmes “performed his usual ‘magic’,” says McLean-Fiander, “creating all the whizzy features now available to our users.”

What we see, what they saw

MoEML captures an image of London just before it was transformed by immigration from a small city of 50,000 in 1550 to a metropolis of 400,000 in 1650.

“Shakespeare came to London as part of that social phenomenon, drawn there by the opportunities afforded by a growing population and the new cultural industry of public playhouses,” says Jenstad. “We can think of the Agas map as a picture of London as Shakespeare might have first seen it. Imagine him as a young man on one of those roads converging on the city. The Agas map doesn’t represent ‘Shakespeare’s London,’ per se, but the London that Shakespeare and his contemporaries transformed.”

MoEML maps approximately 1,600 “locations” including taverns and playhouses; water cisterns and fields; wards or districts; churches and bridges; and of course the streets of London. The map also shows bear-baiting houses; boats on the river; women laying out laundry to dry; people playing or working in the fields; and more.

Jenstad describes the top third of the map as similar to a landscape painting, with a vanishing po#8747; the bottom third is a bird’s eye view; and the section in the middle (bounded by the city wall) is map-like, with no difference in distance perception from one feature to another.

She also points out there were “no hot air balloons or helicopters” for an aerial view of early modern London; no one had a bird’s vantage point. She adds, "It would be remarkable to see this view of ‘London from above’ for the first time. The tradition of making maps by laying out the streets using a grid system was still 100 years in the future.”

Hands-on learning experiences

Not only can we see firsthand what it might have been like to stroll past the same taverns frequented by the players of Elizabethan dramas, UVic students can also enjoy firsthand learning opportunities, thanks to MoEML.

From encoding, research, markup and copy editing to production of editorial style guides and training documents, over 30 UVic undergraduate and graduate students have worked on the project to date; most of them are now working in digital humanities fields, publishing, teaching, programming, project management and web design.

MoEML has developed an innovative Pedagogical Partnership Project. “We team up with professors and students from around the world, supply teaching materials, Skype into their classrooms to offer support, and have the students research and write original scholarly content about places on the map under the close supervision of their onsite professor,” says McLean-Fiander.

The MoEML team then edits, encodes, and publishes the resulting work produced by these international student contributors.

Saturated with multiple layers of research

An exemplar of digital humanities research, MoEML offers its users an array of texts, analysis, reference and background material. The team built up these layers using literary evidence, as well as ground plans, other maps, long views, and visual, historical, and legal sources.

The quest to find navigational hot spots might prompt people to want to stand exactly where Shakespeare might have once stood—there’s a “ritualistic significance to standing on the same spot,” suggests Jenstad—but now it would be 12 feet below our feet. London is a city that has been mapped since the 1500s and Jenstad doesn’t think we’ll ever get it all right. “I really look at the map with a critical eye now. We’re coming at it not as cartographers, but as textual scholars.”

Besides the map interface, MoEML includes an Encyclopedia (with databases of people, places, topics, terms, and sources) and a Library of primary source texts, including a selection of dramatic extracts and a versioned edition of John Stow’s Survey of London (1598) that richly describes the monuments, real estate, and other significant reference points of the early modern city.

MoEML Library texts are encoded in an XML language developed for literary texts by the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) which is industry standard for text encoding.

Toponyms and a gazetteer

MoEML also includes a descriptive Gazetteer (dictionary) of London placenames. Jenstad describes it as “less flashy than the map, but it is a very significant piece of scholarship that depends on 10 years of work carefully tagging tens of thousands of toponyms.”

The Gazetteer lists all the variant names and variant spellings of 1,500 toponyms or placenames in early modern London. It is the first gazetteer of its kind and makes it possible to search large databases for placenames and to identify toponyms generally. Until now, such identification wasn’t reliable because many places have multiple names and spellings are highly variable.

Every variant is now listed alphabetically; it can be found regardless of form or spelling. For example, Upchurch, Apechurch, and Vpchurch all refer to the same place and thus can all be found in the gazetteer entry for Abchurch Lane.

Placenames include the now familiar Fleet Street and Drury Lane, but also Curtain Road, Garlick Hill, Dead Man’s Place and even Pissing Alley.

More on MoEML

Major funding for MoEML was provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and the Canada Foundation for Innovation, with principal support from the HCMC.

UVic is a leader in the field of digital humanities. Its English language and literatures programs are ranked in the top 200 in the world by the QS Subject Rankings.