One student's grand view of the smallest things

- Julia Bobak

Invisible worlds exist all around us. And UVic biology undergrad James Tyrwhitt-Drake has made it his mission to reveal the smallest of those worlds, with spectacular results.

The invisibility of microscopic creatures, much like the perceptual invisibility that comes with the speedy flapping of a hummingbird’s wings, requires special equipment to capture and appreciate. For Tyrwhitt-Drake, that equipment is the scanning electron microscope (SEM) in UVic’s Advanced Microscopy Facility.

Tyrwhitt-Drake’s enthusiasm is contagious: he thinks of himself as a “science artist” and explains the motivation behind his work in grand terms. “I just want to show everyone that the world is beautiful.”

“We so often use technology as simply a tool for comfort,” he clarifies, “but it can also be used as a window into other worlds; into the worlds around us that the human body cannot experience unaided.”

The microscope isn’t Tyrwhitt-Drake’s only medium. In his first year at UVic, he downloaded photographs of the Earth taken from the International Space Station and compiled them into a time-lapse video that feels like flying over the planet at night. On YouTube, Tyrwhitt-Drake’s video has been viewed over seven million times. “That’s when I knew I could change the world.”

Turning his attention to smaller scales allowed him to merge his interests in art and cell biology. After attending a workshop offered by the Advanced Microscopy Facility, Tyrwhitt-Drake learned to use the SEM and began volunteering with the facility in exchange for time on the instrument. An SEM works in a similar fashion to an optical microscope, but uses a beam of electrons in place of a light beam. Though it requires more expensive equipment and considerable operator expertise, the SEM also yields remarkably high-resolution images.

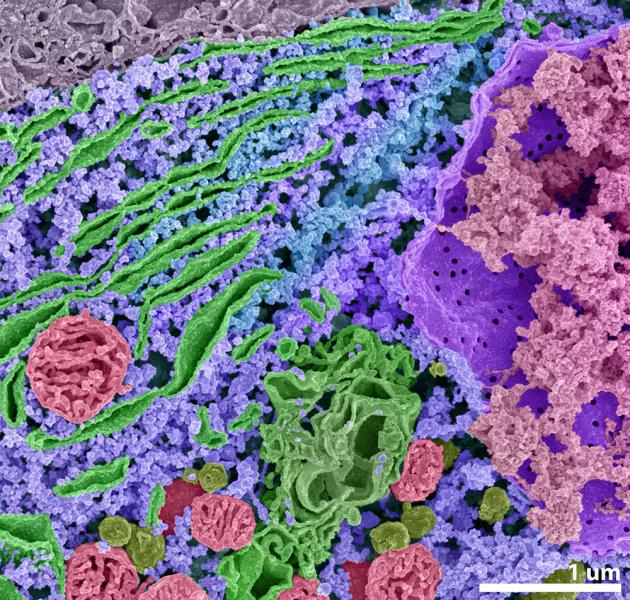

The resulting images are the combination of scientific prowess, artistic vision and commitment to detail. And for all his grand ambition, Tyrwhitt-Drake seems driven at least as much by curiosity. “I wanted to see just how much information I could extract from the microscope.” Using complex strategies like image stitching and depth stacking, he was able to create poster-sized high-resolution images with hundreds of megapixels and short animations revealing the greater context of his specimens. This has yielded images like that of a single mouse neuron cell, with each biological component painstakingly coloured, which James estimates took a hundred hours of work to produce.

Another image, of a diatom, a unicellular type of phytoplankton, graced the cover of the Microscopy Society of Canada bulletin in 2013. An animated version of the same sample found its way to the website of the Smithsonian. The public seems hungry for just this mix of discovery and infinitesimally minute beauty.

Though he could graduate this spring, Tyrwhitt-Drake plans to stay at UVic for an additional year to take directed studies in electron microscopy. He is hoping to further his work with the SEM and perhaps even learn to use the most powerful microscope in the world–UVic’s scanning electron transmission holography microscope–to investigate DNA on an atomic level.

Tyrwhitt-Drake’s art is poised advance in new directions, as well: he’s looking to 3D printing as a means to produce sculptural representations of biological samples. We can’t wait to see what the future holds.