James Webb telescope offers rare glimpse of young planet

A Canadian-led team of international astronomers has made a groundbreaking discovery about how young planets form and grow using a creative approach with unique tools of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

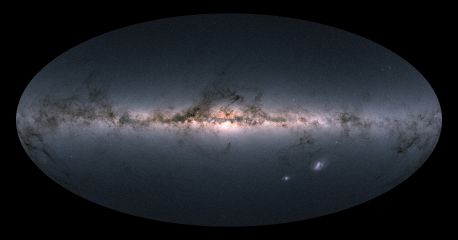

The telescope was used to study PDS 70, a young star orbited by two growing planets. This remarkable system, located 370 light-years away, gives scientists a rare chance to see how planets form and evolve during their earliest stages of development. JWST, using “interferometry mode,” provided unprecedented details about the planets and the swirling disk of gas and dust they’re forming within. The findings published in the Astronomical Journal on Feb. 12 offer a fresh perspective on how planets grow over time, competing with their host stars for material.

This is like seeing a family photo of our solar system when it was just a toddler. It’s incredible to think about how much we can learn from one system.”

—Dori Blakely, a University of Victoria PhD candidate and research lead author

The team’s findings provide evidence that planets wrangle with their host star for material, supporting the idea that planets form through a process of “accretion,” pulling in mass from the gas and dust around them.

The discoveries give astronomers a clearer picture of how planets and stars form and evolve together. And by watching these planets grow and interact with their environment, scientists are learning how planetary systems—even our own—came to be.

Seeing planets in the act of accreting material helps us answer longstanding questions about how planetary systems form and evolve. It’s like watching a solar system being built before our very eyes.”

—Doug Johnstone, principal research officer at the National Research Council of Canada’s Herzberg Astronomy and Astrophysics Research Centre

Blakely and the team studied PDS 70, a relatively young star—about 5 million years old—that is surrounded by a disk of gas and dust flattened out like a pancake, with a large gap in the middle where two planets, PDS 70 b and PDS 70 c, are taking shape.

To get such a clear view of the planets, the team used JWST’s Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph, placing a special mask with several tiny holes over the space-based telescope that allowed a small fraction of light to pass through—essentially “turning down the young star’s blinding spotlight so you can see the details of what’s around it,” according to Prof. René Doyon, director of the Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets and principal investigator for JWST’s NIRISS instrument.

This approach allowed the team to uncover features that traditional telescope imaging can’t detect and shows how JWST is revolutionizing the way we study planets and their origins.

-- 30 --

Photos

Media contacts

Dori Blakely (Dept. of Physics and Astronomy) at blakelyd@uvic.ca

Nicole Crozier (Science Communications) at scieco@uvic.ca

Jennifer Kwan (University Communications and Marketing) at uvicnews@uvic.ca

In this story

Keywords: astronomy, research, partnerships, space, technology, administrative, student life, physics

People: Dori Blakely, Doug Johnstone