Unique carnivorous sponge discovered

- Mitch Wright

When you’ve discovered dozens of new species, it takes something more than a little unusual to spark excitement. For Henry Reiswig, UVic adjunct professor of biology, the images of a candelabra-shaped “something” was enough to snare his curiosity and turned out to be a previously unknown species of carnivorous sponge.

The remarkable photos and specimen were sent several years ago by Dr. Welton Lee, a sponge specialist at the California Academy of Sciences, with the simple query: “Henry, what is this and what do we do with it?”

“I knew it was something new when I first saw the picture,” says Reiswig, who is also a research associate at the Royal B.C. Museum, and the Pacific Coast’s go-to guy for sponge expertise. “I didn’t particularly know it was a sponge, but I had a pretty good feeling.”

That initial gut feeling from the specimen—two were collected in 2000 and 2005 off northern California by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI)—eventually proved out. The results of the investigation—by Resiwig, Lee, Dr. Bill Austin of the Khoyatan Marine Laboratory in North Sidney, and Lonny Lundsten, a senior research technician at MBARI—are already online, and due to be published next month in Invertebrate Biology, the journal of the American Microscopical Society.

Despite discovering some 50 new species throughout his career, Reiswig, who retired to Victoria 10 years ago after a 29-year career at McGill, had never come across anything quite this unusual.

Carnivorous sponges were first identified as such in 1995 and now number about 130 species, or roughly 1 per cent of the 9,000 species of sponges. Most resemble a feather or bottlebrush, says Reiswig, who describes the creatures as “anorexic” due to their thin body structures extending 5–10 cm vertically.

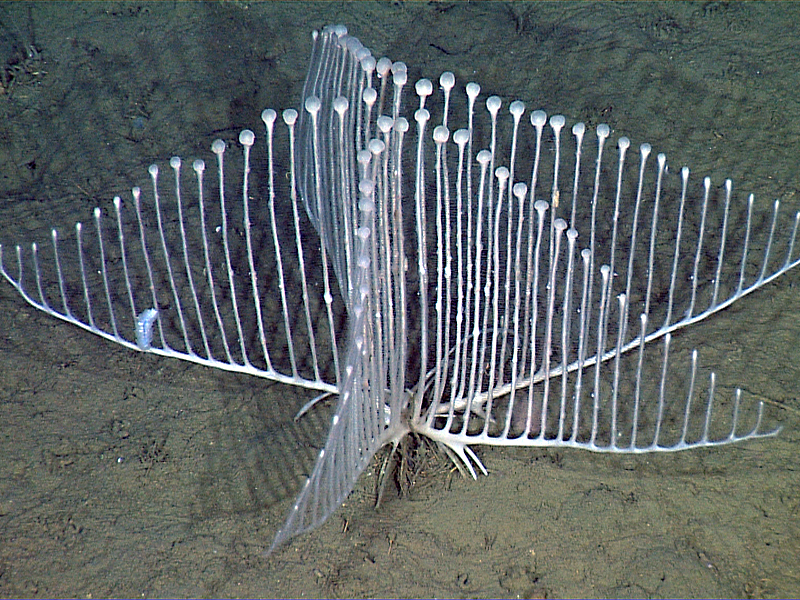

This newfound species—Chondrocladia lyra or “harp sponge”—is different, with five spindly arms radiating roughly 40 cm in a horizontal star-shape, each supporting numerous, evenly spaced tendrils reaching vertically in parallel some 30 cm.

The researchers conclude the terminal globes at the upper tip of each upright branch, which produce sperm, are also buoyant, enabling the branches to grow perfectly vertical—a highly unusual trait for marine animals.

“It’s spectacular,” says Reiswig. “It is totally alien, unlike any organism known on earth. There’s nothing like it ever seen.”

It’s not just body structure that sets this sponge apart, though. It has evolved to eat larger prey—“around 0.5 mm, not large by human terms, but compared to marine bacteria these are blue whales,” says Reiswig—and rather than broadcasting its sperm to reproduce, it releases sperm “packages,” which vastly prolong sperm life to extend its potential mating reach, and avoid wastage.

“It really sets them aside from other sponges. This opened them up to deep-sea environments,” says Reiswig, noting the specimens he examined were found at 3,300 metres.

Video of harp sponge: http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_profilepage&v=VC3tAtXdaik