The power of waves

A First Nation is trying to get back to its ancestral land through an ambitious project: harness the ocean to create energy.

Text and photos by Camille Vernet.

Originally published as “Le pourvoir des vagues” on CBC Radio-Canada Nov 27, 2023.

Translated from the original French. Republished with permission from the author.

"My grandfather's last will was that I stay here. So I remain," says Darrell Williams Jr., a member of the Mowachaht-Muchalaht First Nation, one of the last inhabitants of Yuquot, on Nootka Island.

Of what was a much larger and tightly-knit community, there is only one family that now lives on this island off British Columbia.

The Mowachaht-Muchalaht First Nation fervently wishes to reclaim this ancient village, whose members were forced to move away in the 1960s.

The power of waves, an abundant renewable energy source that draws its strength from the surrounding island environment, could bring this Indigenous community closer to its goal.

The energy of the ocean

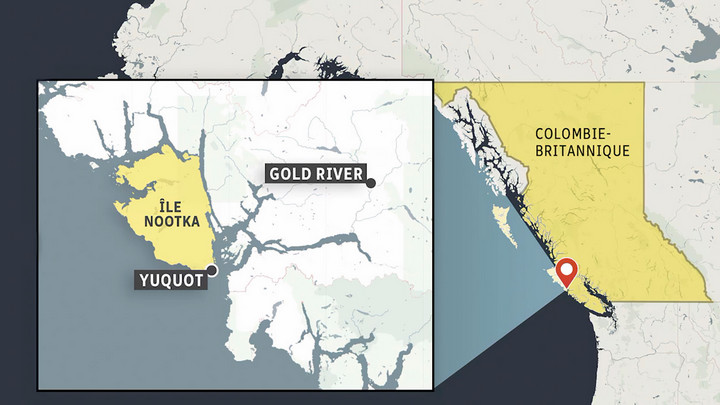

The Pacific Ocean fiercely hammers the cliffs of Nootka Island, located at the outskirts of the western end of Vancouver Island.

"We're at the end. The next stop is Japan," says Roger Dunlop, while manoeuvring a fishing boat in heavy rain. The Mowachaht-Muchalaht First Nation Land Management Officer serves as a guide for the day.

One hand on the helm and the other on the handle of his cup of coffee, he does not seem disturbed by the crashing waves that rock us up and down.

On board, Riley Richardson, a researcher at the Pacific Regional Institute for the Discovery of Marine Energy (PRIMED), University of Victoria, is firmly attached to the side of the boat. It is the force of the waves, which leaves the passengers pale in the face, that he tries to evaluate.

The ship stops in the middle of the ocean, which stretches as far as the eye can see. Only a small yellow buoy is visible on the horizon. "It measures the time that elapses between the two peaks and the direction of the waves," explains the researcher.

Wave energy, which harnesses the energy of the swell's movement, is at the center of his research. "The advantage of the energy produced by the waves is that it can travel over hundreds of kilometers with a very small loss," he says.

This energy source should not be confused with tidal energy, which results from the harnessing of tidal movements.

The researcher hopes that the project will produce enough electricity to meet the needs of some 40 homes in the village of Yuquot.

In the Indigenous language, Yuquot means "where the winds blow from all directions."

Storms are common in winter. "That is what we are trying to harness, whether they are storms in the North Pacific or closer to the coastline," says Riley Richardson.

The project is still at the research stage, but if it materializes, it could pave the way for other communities.

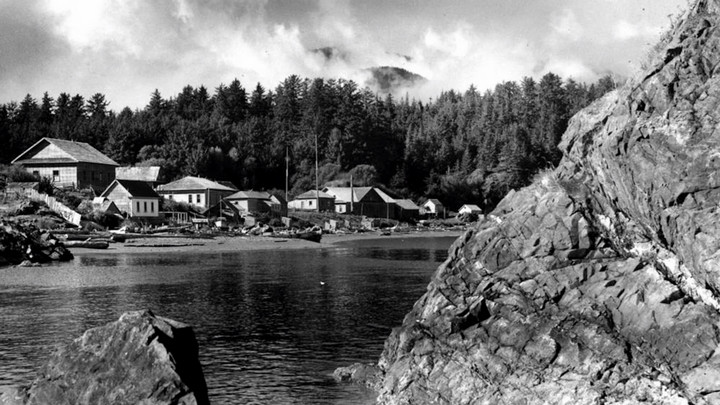

Roger Dunlop docks in the calm waters of the bay. We're in Yuquot. "It is the summer village of the Mowachahts. People lived there until the 1960s/1970s, and it is where the community aspires to return," he says, before disembarking from the boat.

Yuquot is a historical site, classified as a national heritage site. For more than 4,300 years, it was the capital for 17 First Nations in the Nootka Strait. Then, in the 18th century, the bay became a meeting place between First Nations and European explorers and traders, and an important commercial and diplomatic center.

Of what was once a vibrant fishing community, there remain only three inhabitants, a few houses, a church and a lighthouse.

The Williams family house faces the ocean, nestled in Friendly Cove Bay.

Life in Yuquot

For 15 years, Darrell Williams Jr. has lived in this remote landscape about an hour's boat from the town of Gold River.

With the exception of tourists who are passing through in the summer, life on the island is full of solitude. "During the winter, we don't see anyone unless we go to the city," explains Darell, who lives with his 19-year-old son and his father.

There is no cellular reception or connection to an electrical network. Despite the presence of solar panels, during our visit, electricity does not work in the house, because the generator is broken.

Only sunlight punctuated by dark clouds illuminates Darrell's living room. "We had a wind turbine, but it kept breaking down," he says.

Hanging on the wall, a photo shows Ray and Terry Williams, his grandparents, on a four-wheeler, with radiant smiles on their lips. It is in tribute to his grandparents, who have recently died, that he has committed himself to living here.

Darrell's dark eyes light up when he speaks of his grandfather. "He was the most sociable person I've ever met."

Ray dreamed of seeing the community reborn. "He would have liked the energy project with the waves to come to fruition. He had a lot of hope, but he couldn't be there to see him," Darrell says.

Attached to the territory, his grandparents resisted the many incentives to move.

An uprooted community

The majority of Mowachaht-Muchalaht First Nation members are now settled a few kilometres from Gold River in the village of Tsa'Xana.

In the 1960s, the closure of essential services, the lack of maintenance of infrastructure and the decline of the fishing industry contributed to their exodus.

"They closed the school, and everybody had to move," says Edward Jack, who lived on the island as a child.

Several Elders in the community, who lived in Yuquot as a child, testified to the shock suffered at the time of their departure.

Anthony Dick left the island at the age of eight. "I had no choice. Our parents had no choice," he says. "It was my playground. I grew up in the vicinity. I knew every rock I climbed on."

Margaret Rose Amos lived in Yuquot until she was 13. She says that many members of the community lived on fishing at the time. "They started losing their boats. My father lost his two boats to a storm. As a result, he was no longer employed."

The promise of new housing and jobs at the Ahaminaquus pulp and paper mill on Vancouver Island, some 50 kilometres from Nootka, also prompted community members to leave.

However, the reality of life in Ahaminaquus, on the factory floor, has proved far from promise. "It was horrible," recalls Margaret Rose Amos.

"We lived with the sawdust and the factory smell. We could never leave the windows open. We couldn't hang the clothes. The children weren't playing outside. We couldn't bathe in the water anymore because it was polluted, there weren't many fish left," she says.

Jobs at the promised pulp and paper mill have only materialized for a handful of First Nation members, as described in an article published in the academic journal American Studies (AMSJ) in 2006.

The community that had moved for better living conditions and stable jobs had found themselves in a much worse situation than before.

The article also states that, after repeated complaints about health problems related to breathing, water contamination and inadequate housing conditions, a second relocation took place in 1996.

This time it was near Gold River, about 15 miles from the coast. "We had never lived in the mountains, we had always been on the ocean," says Anthony Dick.

When asked how he feels when he thinks about Yuquot, he says "Homesick. I've always wanted to go home to Yuquot."

All the Elders we met are unanimous: it's their home.

Some Elders are eager to return to Yuquot, while for others the lack of access to services, including health care, would be too difficult.

However, despite the years that have passed, their commitment to Yuquot has not wavered. Every summer, the community gathers there. "I miss that a lot. When I'm there, I go where I grew up, where my house was," says Edward Jack.

It is the determination of the First Nation that motivates researcher Riley Richardson. "When we talk to members of the community, we really realize how important this place is to them."

In an email, Aboriginal Services Canada stated that some members may choose to live in the historic village of Yuquot, but that to date none of Mowachaht’s leaders have made any requests concerning the infrastructure of the village of Yuquot.

An environment to be protected

The boat ride through the bay is punctuated by encounters: a group of seals lounging on a rock, a whale diving on the horizon, its tail rising high in the sky before hitting the surface of the water, or a sea otter having fun.

"You missed the killer whales this morning. There were three of them," says Darrell Williams Jr., with his eyes on the shore.

In an effort to preserve this immaculate environment, he is not the only one to ask: what will be the impact on the marine life from this renewable energy project?

"I have concerns about wild animals," he says. The wave energy device, which will capture energy, will be moving underwater, which poses a risk of collision for marine mammals and fish, while generating underwater noise.

"With a single device, the impact is not expected to be significant on marine life," says Riley Richardson. "We're going to deploy a hydrophone to learn more about whale movements in the region and then design a device that mitigates environmental consequences."

The chosen device was developed by the California company CalWave. Two representatives are part of the expedition to better understand the environment in which the device will be installed.

In 2021, the company launched a six-month pilot project off San Diego. The device moves with the motion of the waves, from the top of the water to the floor of the ocean, where it is anchored with a cable. When moving underwater, energy is converted into electricity, in the same way as regenerative braking works in an electric car.

A technology that needs to prove itself

Work to master this source of energy has been under way for more than two centuries. The very first patent, entitled Various Ways to Use Waves as Engines, was registered in France in 1799.

The ocean is the greatest reserve of this energy, but it is a brutal environment.

"Salt water is corrosive. It's difficult from an engineering point of view to design materials and machines capable of effectively resisting corrosion and harnessing this energy to convert it into electricity," explains Riley Richardson.

Wave energy is still in the development stage. Costs are therefore still high compared to other renewables, according to the Surfer on the Wave Report: Challenges and Opportunities for Marine Renewable Energy in the Transition, University of British Columbia.

It will take time for this energy to be sufficiently efficient and cost-effective to enable large-scale deployment.

The project received federal support in 2021, as well as an additional contribution from TD Bank in the amount of $1 million. Research can therefore continue until 2025. "We will then have all the information we need to enable the Nation to decide whether or not to continue the project and try to secure funding for construction," says Riley Richardson.

Wave energy would be of particular interest to coastal communities that are dependent on diesel and seek to make the transition to cleaner energy.

"It offers maximum availability in winter, where demand is highest in British Columbia. Conversely, solar energy is more available in summer. There is therefore an excellent balance between these two renewable energies," says Richardson.

Rebuilding a village

This energy project represents a first step long awaited by the community. It is part of a broader approach, which aims to boost the commercial fishing industry and boost the tourism industry.

"Part of the project is to develop the economy," says Roger Dunlop.

This achievement is essential, not only for those who aspire to return to Yuquot, but also for those who have remained there.

To get a few hours of power, Darrel Williams Jr. starts his backup diesel generator. The sound of the sweeping waves mixes with the rumble of the machine.

"I heard that a few people wanted to settle here. The father of a friend of mine is going to build a hut near us. It would be nice if he came here," he said.

It will take much more than a renewable energy project to restore what has been lost, but what is certain is that the will of this First Nation to return home will continue. A driving force as powerful as the ocean.

This text is part of Human Nature, a series of content that presents change actors that have a positive influence on the environment and their communities in British Columbia.

Watch the video